In a new paper, my former Tax Policy Center colleague Daniel Berger and I calculate that the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) modestly reduced the cost of tax expenditures in the individual income tax and made them slightly less regressive. We estimate that in tax year 2019, individual taxpayers will receive about $1.2 trillion in benefits from tax expenditures, taking account of interactions among provisions.

Overall, high-income households received most of the benefits of the TCJA, thanks to cuts in individual and corporate tax rates, the increase in the exemption from the individual alternative minimum tax, and the new 20 percent deduction for qualified income of pass-through businesses. But those high-income households did lose some of the benefit of tax expenditures.

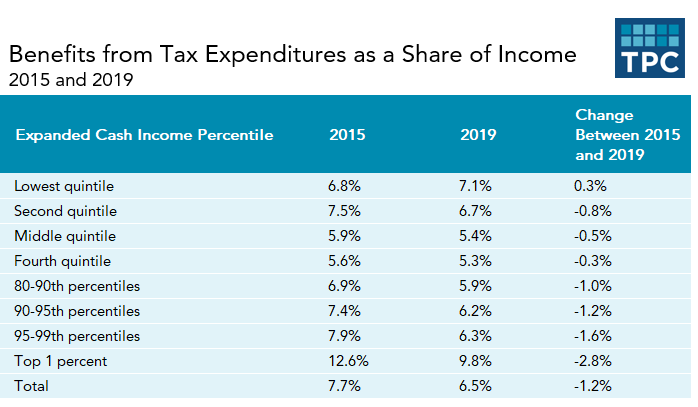

Households in all income groups benefit from tax expenditures, but those in the top 1 percent of the income distribution receive the largest benefits – about 9.8 percent of their income, compared with 6.5 percent of income for all households and 5.4 percent of income for middle-income households. Households in the bottom quintile fare slightly better than average, with benefits of about 7 percent of income.

The highest income households benefit the most from tax preferences for capital gains and dividends, which are taxed at lower rates than wages and interest income; and from the exclusion of most capital gains on sales of principal residences and gains on assets transferred at death. Middle and upper-middle income households benefit most from exemptions from taxable income of employer sponsored health insurance (ESI) and income accrued within qualified retirement plans. The lowest income households benefit most from refundable tax credits, including the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, and the credit for premiums for health insurance purchased through the exchanges established by the Affordable Care Act.

The TCJA made substantial direct and indirect changes to individual tax expenditures. The $10,000 annual cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, the increase in the standard deduction, and lower marginal income tax rates all reduced the benefits of tax expenditures.

Of course, the SALT deduction cap did so directly. The higher standard deduction and lower marginal tax rates indirectly reduced the benefit of other itemized deductions and exclusions.

While the TCJA did not change the preferential tax rates on capital gains and dividends, lower marginal rates on ordinary income reduced the tax benefits of special rates for investment income and the exclusions of housing gains and capital gains transferred at death. These reductions in tax expenditures were offset in part by some increases in tax expenditures, including the expansion of the child credit and the new deduction for owners of pass-through businesses such as sole proprietorships, partnerships, and subchapter S corporations.

Mainly due to TCJA, tax expenditures as a share of income will decline between 2015 and 2019 for all income groups except the bottom 20 percent. They will fall the most for taxpayers in the top 1 percent largely due to the SALT deduction cap and the reduction in marginal rates that reduced the value of their preferences for capital gains and dividends, itemized deductions, and exclusions.

The decline for other taxpayers in the top 20 percent is mainly due to a reduction in the value of itemized deductions from the SALT cap, lower tax rates, and the higher standard deduction. The increase in tax expenditures in the bottom quintile is due to the expansion of the refundable portion of the child credit.

Tax expenditures in the individual income tax law remain costly and while they benefit people at all income levels, they still provide relatively more benefit to the highest income taxpayers. The TCJA only modestly changed this pattern. And if our analysis included corporate tax provisions, the story would look even more favorable to upper income households.