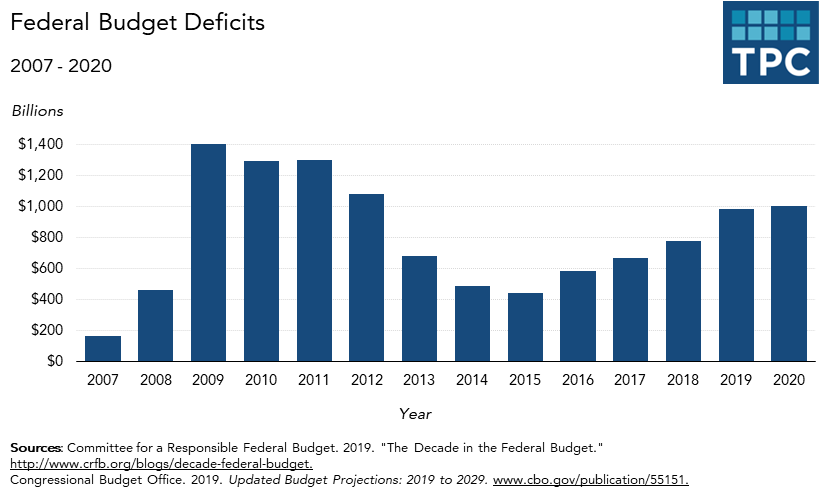

There are ugly charts, and then there is this, courtesy of the folks at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Over the past half-decade, in period of solid—if unspectacular—economic growth and historically low interest rates, the federal budget deficit has been going up. And up. And up.

That is not how it is supposed to work. In normal fiscal times (if there is such a thing), deficits are expected to rise when the economy slows and fall when times are good. Now, it seems, they rise even when the economy is at full employment.

Here’s the story this figure tells:

Ten years ago, in the teeth of the Great Recession, federal budget deficits predictably exploded. Tax revenue fell. Spending for anti-recessionary programs such as Medicaid and food stamps rose with unemployment. Government temporarily cut income and payroll taxes and increased spending for programs such as public infrastructure, all of which added fiscal stimulus.

There was nothing unsurprising or particularly worrisome about any of that. And for the next six years, as the economy recovered, the temporary tax cuts (mostly) expired, and Congress adopted some constraints on spending growth, annual deficits fell back to pre-recessionary levels.

But starting in 2015, all that reversed again. Congress abandoned even modest attempts to control discretionary spending growth. At the same time, it cut taxes in early 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019—reducing federal revenues by a combined amount of nearly $7 trillion over the 10 year period following passage of each of the bills.

There is no evidence that any of those tax cuts significantly improved an economy already nearing (or at) full employment, despite the fervent promises of their backers. Nor have the tax cuts come remotely close to paying for themselves, as some of those same promoters claimed.

In effect, Democrats and Republicans engaged in a cynical bargain to buy votes. They gave away money they did not have to lavish benefits on constituents who, for the most part, did not need it.

There are so many examples, but here are just two:

- In December, Congress restored special interest tax breaks to subsidize economic activity that occurred as long ago as 2017. Targeted tax breaks are supposed to create government incentives to encourage specific future economic activity. But in this case, Congress agreed to pay businesses retroactively by restoring expired tax benefits covering activities that occurred two or three years ago. This has zero incentive effect on the activity it is intended to promote. It is nothing more than a cash windfall to favored taxpayers.

- President Trump raised tariffs on goods imported from China. The Chinese government responded by imposing new import taxes on US agricultural products such as soybeans. To help mollify the farmers who lost sales to China, Trump opened the federal trough and gave them $28 billion in cash payments and other subsidies. According to one analysis, just 82 agribusinesses got more than half the money.

So far, runaway full-employment budget deficits have had little impact on interest rates that remain at historically low levels. But those borrowing costs won’t stay low forever. Nor will the economy grow forever. As the chart shows, when the economy tanked in 2008, Congress and the White House had room to open the fiscal policy spigots even as the Federal Reserve was driving down interest rates. Those combined fiscal and monetary weapons likely curtailed the recession and helped restore economic growth.

But with interest rates already low, the Fed will have few policy levers to pull when the economy sags. And all of those recent tax cuts and spending hikes may have limited the government’s ability to use fiscal policy to put out an economic brushfire. The federal debt already is at about 80 percent of Gross Domestic Product and the Congressional Budget Office projects it will reach 100 percent by decade’s end, assuming continued modest economic growth. We have not seen that level of debt since the US was paying off the cost of World War II.

Will a future Congress and president still be able to borrow to cut taxes and boost spending in the teeth of the next recession? I suppose it’s possible. But I’m not certain. And that is…worrisome.