The Biden administration’s plan for broad-based student loan forgiveness of up to $20,000 per individual won’t affect borrowers’ federal tax bills, but it could have state tax implications for some.

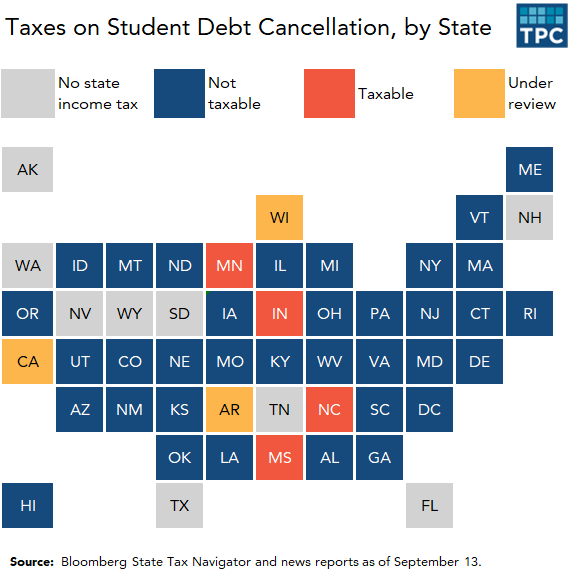

While many states will follow the federal lead and not treat forgiven student loans as earned income, some could take a different path. At this time, four states plan to treat forgiven student loans as income, while three states are reviewing their tax rules.

What is conformity and why does it matter for student loans?

This all comes down to how states define taxable income. Most states with an income tax use, or conform to, the federal definitions of taxable income or adjusted gross income (AGI) for calculating state income taxes.

The vast majority of states that have an income tax (34) will not tax forgiven student loans because they “conform” with federal definitions of income. While forgiven debt is usually treated as income, last year’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) explicitly exempted student debt forgiven between 2021 and 2025. But not all states conform to the current version of federal tax laws.

If a state uses the current definition of federal AGI—"rolling conformity”—then forgiven student loans are not taxable under these states’ income taxes. However, if a state conforms with federal rules as defined before March 2021—“static conformity”—forgiven student loan debt will be treated as taxable income. Minnesota and Wisconsin both use an older definition of federal AGI and must update their conformity date if they want to exempt student debt forgiveness. Other states that conform to pre-ARPA tax laws include California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Wyoming.

Then there are some states that don’t use federal taxable income or AGI: Arkansas, New Jersey, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania. These states use a variety of federal definitions—simplifying state tax filing—but there is no direct link to the larger federal code, so whether forgiven student loans are taxable will depend on the state’s executive or legislature.

In Pennsylvania, existing state law exempted narrow forms of student loan forgiveness from state tax, and Governor Tom Wolf said the exclusion will apply to federally forgiven student loans from Biden’s executive order.

Mississippi went in the other direction, confirming that forgiven student loans will be included in Mississippi taxable income.

Arkansas, California, and Wisconsin said clarifications are forthcoming—so these states could still change how they treat forgiven student loans.

Updates to student loan balances are expected to start hitting borrowers’ accounts before the end of the year, which means forgiven loans could count towards 2022 income and factor into next year’s filing season. With many state legislatures currently out of session, legislators would need a special session or to work very quickly during their normal sessions next year to enact legislative fixes.

Can and should states tax student debt cancellation?

Anticipating a potentially broad loan forgiveness plan, Congress included the tax exemption in ARPA to prevent beneficiaries from getting hit by a big unexpected tax bill. At the state level, lawmakers must ask whether the exemption is worth the cost.

Because of the way the federal forgiveness is structured, the majority of benefits will flow to people in the bottom 60 percent of the income distribution. Pell recipients, who are the majority among Black and Hispanic students, get the biggest benefits from forgiveness and benefit from it not being taxed by the federal government. Depending on how much income these borrowers currently make, a $20,000 increase in income could translate into a steep tax bill.

State revenues in the first half of 2022 have been strong, and at least 34 states and the District of Columbia already cut taxes this year. States also will not have been expecting additional income tax revenue from the forgiven student loans.

On the other hand, Republican state officials who oppose the loan forgiveness plan—and there are many of them—may also oppose a tax exemption for its benefits.

In the end, that opposition may not matter. The Department of Education has been instructed not report loan forgiveness as income to taxpayers or to the IRS, which would be a major administrative obstacle to states trying to tax the cancelled loans.

Zooming out: When is a good time for states to update tax conformity?

Any time the federal government makes changes with major tax implications quickly—like student loans, or the partial exclusion for unemployment benefits last year—states have to also adjust their own taxes on short timeframes and with limited resources. Not to mention the confusion that sudden federal and state tax changes cause for taxpayers.

Because some states do not automatically conform to federal law, they typically pass conformity updates each year. But the revenue implications of choosing to tax forgiven student loans dramatically changed after Biden’s August announcement, showing that there is no straightforward advantage to acting sooner than later.

For now, borrowers have to deal with the uncertainty surrounding their tax liability while states finalize their tax rules. But at least this isn’t happening in the middle of tax season again.