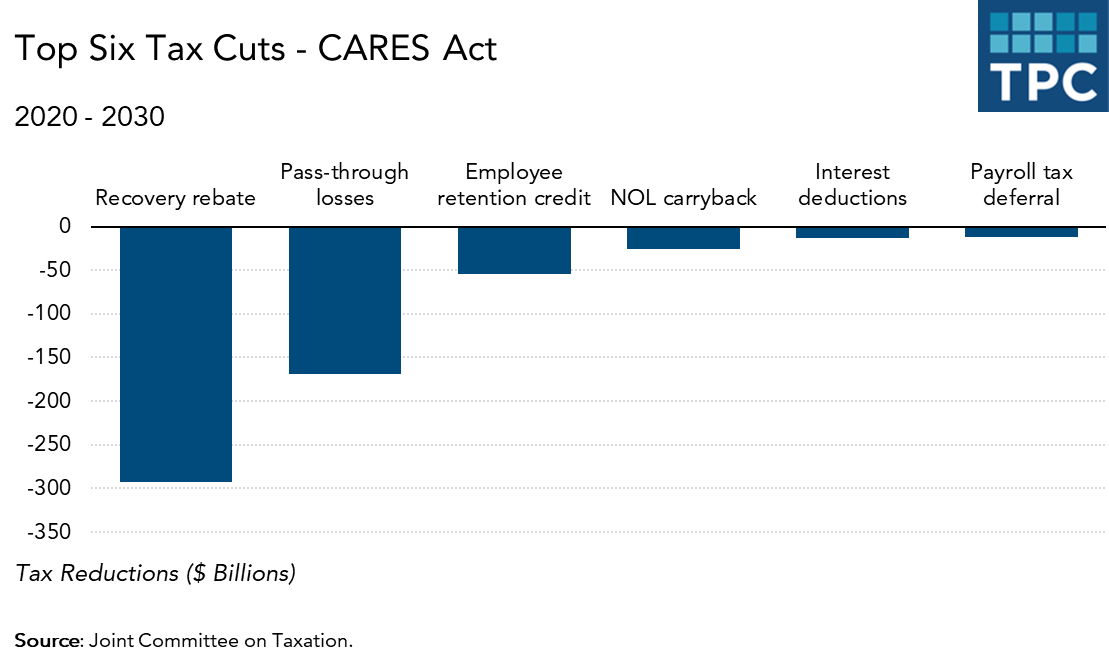

Over the next decade, the individual “recovery rebate” program will account for about half of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act’s tax cuts. Nearly all of the remaining cuts will go to business, although workers may benefit from some of these. More than a quarter of the tax cuts go to taxpayers in the top income decile.

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that recovery rebates will cost $292 billion, or 49 percent of the $591 billion 10-year cost of the CARES Act tax cuts. Households are receiving $1,200 per adult ($2,400 per couple), plus $500 per dependent child under age 17. The payment is phased out for singles with adjusted gross income above $75,000 ($150,000 per couple), targeting the relief toward low and moderate-income households.

The next largest five tax cuts, totaling $276 billion or 47 percent of total CARES Act tax measures, are for businesses. Measures directly benefiting business owners—modifications of the tax treatment of net operating losses (NOLs), interest deductions, and active losses of pass-through entities—account for $209 billion or 35 percent. Two payroll-related measures—the employee retention credit and the employer payroll tax deferral—account for $67 billion, or 11 percent of total CARES Act tax cuts. This relatively modest revenue cost reflects the expected repayment of the deferred payroll taxes in late 2021 and 2022.

The CARES Act loosens several business tax restrictions imposed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), rescinding them not only for 2020 but also retroactively. The largest of these measures, accounting for almost 30 percent of total CARES Act tax cuts, allows pass-through business owners to offset active losses against other forms of income, such as wages and investments, without limit.

The TCJA limited this offset to $250,000 per year for individuals ($500,000 per couple), which significantly raised taxes for a small number of high-income taxpayers who had both extensive business losses and large amounts of other income. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that rescinding this measure for 2018-2020 will predominantly benefit households with more than $1 million in income. Because high-income households are far less likely to spend additional income than lower-income households, this change will generate little if any stimulus, while costing significant amounts of revenue.

The CARES Act also eases TCJA limits on net operating loss (NOL) carrybacks and interest deductions. These changes are unlikely to boost business investment but should improve cash flow, which will help some businesses weather the downturn. These measures are expected to cost $101 billion over the next two years, but just $40 billion over the 10-year budget window, since increased carrybacks of losses and current deductions for interest paid reduce future deductions when these items can be carried forward to future tax years.

The TCJA barred firms from using current losses to offset past profits, whereas prior law permitted firms to carry losses back to the prior two tax years. The CARES Act allows taxpayers to carry back losses incurred during 2018-2020 for five years. This is especially generous because it will allow corporations to amend returns and reduce taxable profits for pre-2018 tax years, when the corporate income tax rate was 35 percent, much higher than today’s 21 percent.

The TCJA also limited interest deductions to 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, depletion, and amortization (EBITDA). The CARES Act raises this limit to 50 percent for 2019-2020 and calculates both years’ allowance on the basis of 2019 EBITDA.

The CARES Act also allows employers and the self-employed to postpone paying their share of Social Security taxes—6.2 percent of wages up to $137,700--through the end of 2020. These taxes must then be paid back over two years. All employers are eligible for this deferral, even if their business is not being hurt by the pandemic.

The employee retention tax credit is more narrowly targeted: Employers that closed operations or lost at least half their gross receipts due to COVID-19 can receive a refundable payroll tax credit of up to $5,000 per eligible employee through the end of 2020. Businesses with more than 100 employees can only claim the credit for inactive employees that are still being paid, while smaller businesses can claim it for all employees.

While permanent payroll tax cuts are likely to eventually benefit workers through higher wages, temporary employer payroll tax cuts are likely to benefit business owners. Firms that are overstaffed during a recession will not increase hiring, so the payroll tax cut will shore up profits (or reduce losses) for owners. Still, that added liquidity may help firms survive the downturn and retain employees who otherwise might be laid off.