This blog has been revised, reflecting TPC’s recalculated analysis of proposals to reduce business taxes that are under discussion in Congress. TPC’s initial analysis over-estimated the revenue loss of these provisions and their benefits to households.

The lame duck Congress will spend the next several weeks arguing over the fate of several key provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the 2021 American Rescue Plan that either have expired or will disappear at the end of this year. A new Tax Policy Center analysis finds that extending them all would reduce federal revenues by about $700 billion from 2023 to 2032. But the distribution of benefits would vary widely, depending on which proposals are enacted.

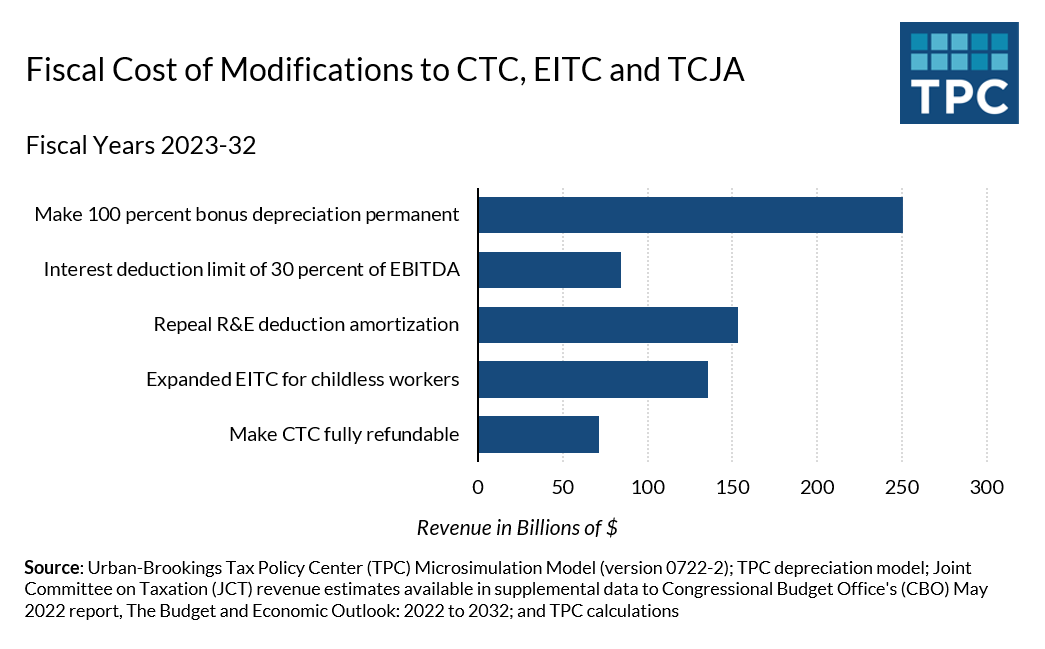

TPC looked at five key elements of a possible agreement: Making the Child Tax Credit (CTC) fully refundable as it was in 2021, restoring the more generous 2021 version of the earned income tax credit (EITC) for workers who don’t live with their children, allowing businesses to once again write off the full cost of research in the year the expenses are incurred, extending more generous “bonus depreciation” of capital equipment, and allowing more liberal rules for firms to deduct interest costs. TPC assumed all those changes would be permanent and retroactive to the beginning of 2022.

$700 billion in lost revenue

Restoring the more generous 2021 version of the EITC and full refundability of the CTC would reduce federal revenues by roughly $200 billion over the 10 years from 2023 to 2032. These changes would almost entirely benefit low- and moderate-income households.

Extending or restoring only the business tax breaks would slash revenues by a bit less than $500 billion and mostly benefit high-income households. Neither Democrats nor Republicans appear to be giving any thought to paying for any of the proposals with offsetting tax hikes or spending cuts.

Of all the provisions, the biggest revenue loss would come from making bonus depreciation permanent. It would lower revenue by roughly $250 billion in the first 10 years. However, since expensing largely results in a change in the timing of tax payments, the revenue loss for the next 10 years (from 2033 to 2042) would drop to about $155 billion.

Who benefits most?

If Congress agrees to all the changes, TPC found the biggest beneficiaries, measured in terms of percent change in after-tax income, would be the lowest-income households. They’d get an average tax cut of 2.1 percent in 2023, or $370. The next highest income group, those making between about $30,000 and $60,000, would see their tax bill fall by an average of about 0.5 percent of after-tax income, or about $200.

Not surprisingly, low-income families with children would benefit the most. They’d see an average tax cut of about $1,000, raising their after-tax incomes by 3.7 percent. Nearly all those benefits would result from restoration of the fully refundable CTC.

At the other end of the income distribution, the highest-income households, those making about $4.4 million or more, would see their after-tax incomes rise by an average of about 0.2 percent. In dollar terms, they’d be the big winners, with their average incomes rising by about $22,000.

Keep in mind that these would not be direct tax cuts. TPC allocates these business taxes to workers and the normal return to capital. Because these high-income households make the highest wages and also own the most corporate shares, they’d receive an outsized benefit from the corporate tax cuts through higher wages and salaries and increased stock prices. However, even low- and moderate-income households would benefit modestly from their share of the corporate tax cuts.

Representative changes

In 2027, after all the individual income tax provisions of the TCJA are due to expire, the overall story is roughly the same, though the numbers change somewhat. TPC found low-income households would receive a somewhat smaller benefit from the fully refundable CTC and EITC expansions. They’d see an overall increase in average after-tax incomes of about 1.4 percent or about $300.

The top 0.1 percent would see their after-tax incomes rise by a bit more in 2027 than in 2023, about 0.3 percent of after-tax income or about $28,000.

Because it is not possible to know which changes, if any, Congress will agree to, TPC analyzed a representative set of provisions. In the end, Congress could decide to only temporarily extend some of the business provisions, rather than continue them permanently. And it could make many different changes to the CTC, such as revising the credit amounts or eligibility rules, or adjusting the refundable portion short of allowing the full credit for non-working parents.

But the new TPC estimates do provide a rough sense of what is at stake in lawmakers’ last-minute policy scramble before the end of the year.