Foreign investors, retirement accounts, and other tax-exempt entities now dominate US stock ownership. This shift has important implications for understanding who wins and who loses from changes to US corporate tax policy such as cuts in corporate tax rates and buyback tax hikes.

In a new paper, my former TPC colleague Livia Mucciolo and I update previous findings to document the plunge in taxable ownership of corporate stock that has occurred over the past several decades. Our study is based on the latest data on US financial accounts collected by the Federal Reserve System.

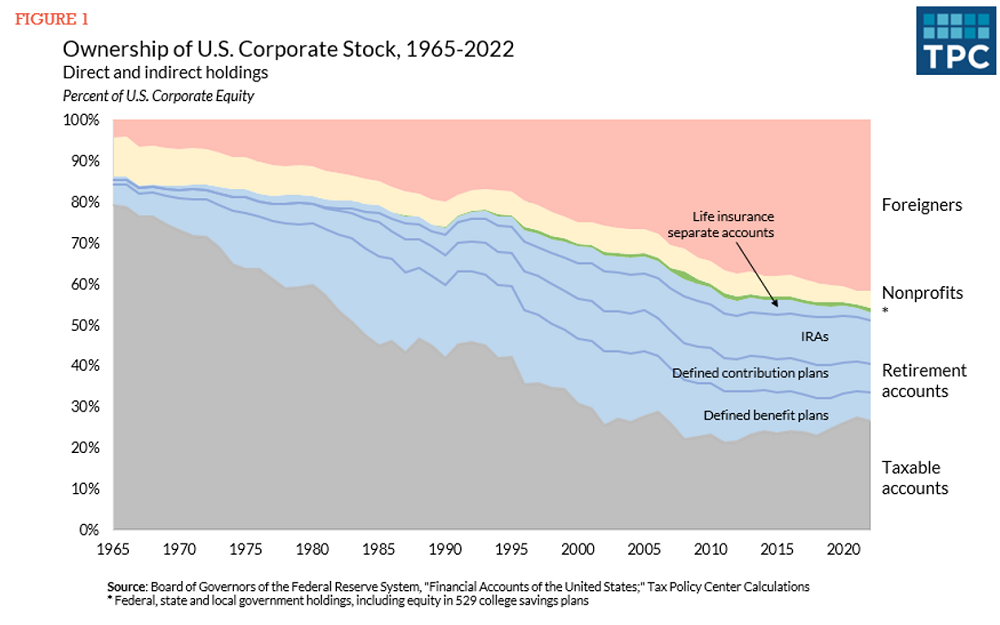

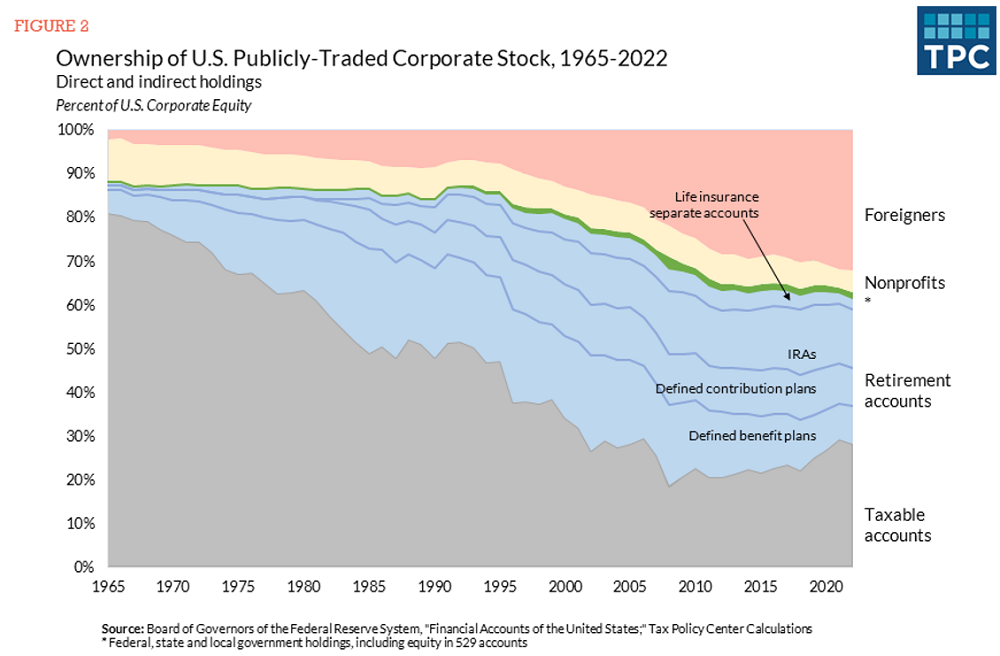

Our main findings: From 1965 to 2022, the share of outstanding US stock that was held in taxable brokerage and mutual fund accounts declined from 79 percent to 27 percent (see Figure 1). The share of publicly traded stock that was held in taxable accounts similarly declined from 81 percent to 28 percent (see Figure 2).

Each of the above figures—total stock ownership and just the publicly traded portion—is important for analyzing different aspects of corporate tax policy.

Knowing how much of total corporate stock is owned by foreigners helps answer how much of the benefit from, say, a corporate tax-rate cut will flow to overseas investors versus domestic ones. Or phrasing the question differently—how much is a corporate tax cut really “America First”?

And calculating the proportion of foreign owners of publicly traded stock helps both analysts and policymakers evaluate the impact of certain policies like the buyback excise tax, since only publicly-traded companies are subject to that tax.

At the end of 2022, foreign investors held the largest single block, 42 percent, of total outstanding US stock (and 34 percent of publicly traded stock). This is likely due, in large part, to US tax policy, including rules that generally exempt capital gains of foreign investors and only lightly tax their dividends.

Domestic retirement accounts are the next largest holder of US stock, accounting for 27 percent of the total and 34 percent of publicly-traded shares. Again, tax policy has played a role: Congress has over the past few decades repeatedly increased the amounts that taxpayers can contribute to tax-deferred retirement plans. (These changes have disproportionately benefited high-income households, exacerbating racial wealth inequities.)

The big shift in stock ownership complicates attempts to tax corporations and their shareholders. Compared to 60 years ago, corporations now pay substantially fewer taxes on their profits, largely as a result of profit shifting to foreign entities as well as lower corporate tax rates. And policymakers who seek, for example, to increase shareholder taxes must grapple with a relatively small and dwindling number of taxable accounts. Widening the base of corporate earnings that are taxed and/or increasing tax rates on those profits, at either the corporate or shareholder level, is the most sensible path forward.