During the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, Congress substantially increased benefits for children, including big boosts in the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and other tax benefits that almost doubled in size from 2018 to 2021. But that’s about to change: In coming years, those enhanced child benefits will fall in real, inflation-adjusted terms and even further as a share of the economy.

Current Congressional questions over whether to restore the 2021 CTC increase are just part of a larger debate over whether kids deserve a higher and more permanent priority in the federal budget. To help put that discussion in context, the Urban Institute’s Kids’ Share Report 2022 starkly reveals the relatively low priority Congress has placed on children in the past and will in the future absent policy changes.

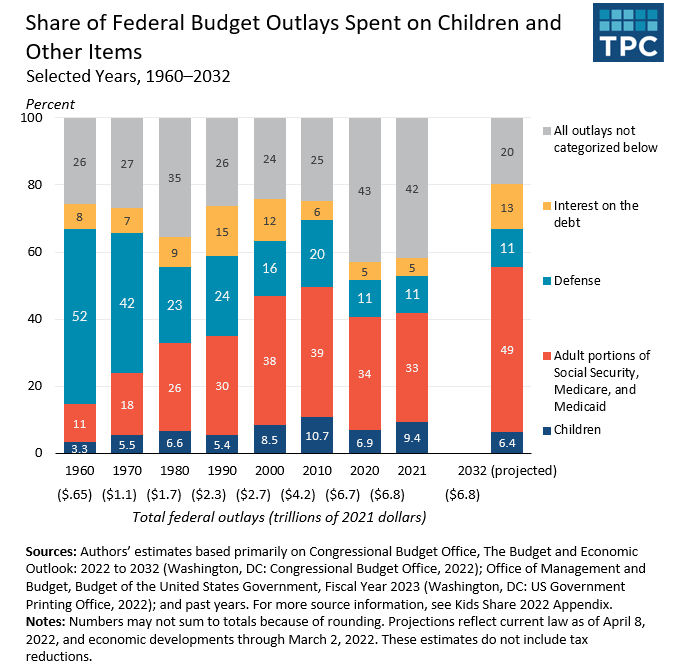

Outlays on children did rise from about 3.3 percent of percent of total federal outlays in 1960 to 6.6 percent in 1980. In 2021, they reached 9.4 percent, approaching another temporarily high level of 10.7 percent attained after the Great Recession in 2010. By 2032, the children’s share of total outlays will return close to the 1980 level.

Outlays for domestic purposes expanded almost everywhere as defense spending declined from 52 percent of total federal outlays in 1960 to about 11 percent in recent years. But outlays on adults through Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid took the lion’s share of this shift by soaring from 11 percent of federal outlays in 1960 to one-third through most of the 21st century. By 2032, that share is expected to grow to half of all federal outlays. Per person benefit increases, not number of beneficiaries, drive most of this growth.

The Kids’ Share report also adds tax expenditures to those outlay totals. Tax provisions are by far the largest source of federal assistance to children. In 2021, tax benefits for kids added up to over $400 billion, including $164 billion from the CTC, $139 in the share of temporary stimulus checks attributable to children, and $57 billion from the earned income tax credit (EITC). This year, total tax benefits for kids are roughly equally divided between tax reductions for those with a positive income tax liability and refundable (outlay) payments for those with no tax liability.

For a variety of reasons, Congress has increasingly turned to tax credits to assist children. The EITC, which mainly supports working families with children, was first enacted in 1975, followed by the CTC in 1997. The EITC always has been refundable—that is, eligible recipients get a credit even if they have no income tax liability. The CTC gradually became partially refundable but was available to those with zero income only during 2021. Over time, both credits were expanded by substantial amounts, though Congress allowed the 2021 expansion to expire.

Meanwhile, the formerly large dependent exemption, which emphasized adjusting tax burdens because larger families have less ability to pay tax than smaller ones, declined in importance and was removed, at least temporarily, after 2017.

This evolution converted tax policy toward children from a simple tax exemption based on family size to one of the most important income support policies of the nation—in effect, the “fiscalization of social policy.”

While both political parties over time have supported both the CTC and the EITC, each also resists expansions to different households. Republicans resist full refundability for those with no earnings, which they believe discourages work by parents. Democrats, by contrast, are reluctant to extend credits to higher-income taxpayers.

The multiple purposes of these two credits—to support work, to support poor families with children, and to adjust tax burdens between larger and smaller families—can be confusing. Each purpose can be justified on the basis of sound principles, but they can also compete when the debate turns to how to spend an additional dollar when only one program, rather than multiple tax and outlay options, is under consideration. For instance, one can generate more CTC support for poor children by disallowing the extent to which the CTC adjusts tax burdens at higher income levels according to family size. A similar debate arises over whether the work subsidies in the EITC should be concentrated on those near poverty.

In the end, Congress has limited tax credit support for children at both higher and lower income levels by limiting refundability, allowing the value of the child credit to erode over time by not adjusting it for inflation, and phasing out EITC supports as earnings tend to exceed poverty levels.

Designing policies for children are challenging. They must be both easy to administer and well-coordinated with other supports for families. But the most important decision is simply whether Congress should make children a greater priority than it has for most of the past half century.