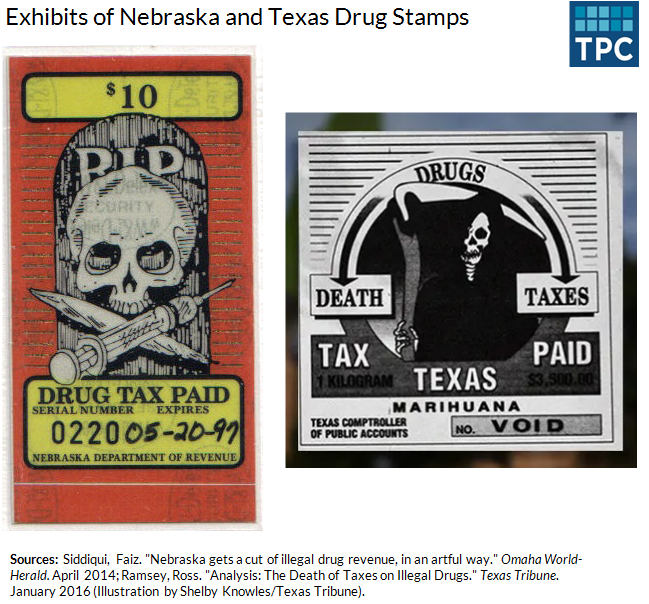

Say you came into possession of some illegal drugs. What’s your next move? According to some states, you should immediately pay the state’s tax on controlled substances. And yes, there is a way to do that. You go to the state’s Department of Revenue to purchase illegal drug tax stamps that become your proof of tax payment—for your illegal marijuana, cocaine, moonshine, etc.

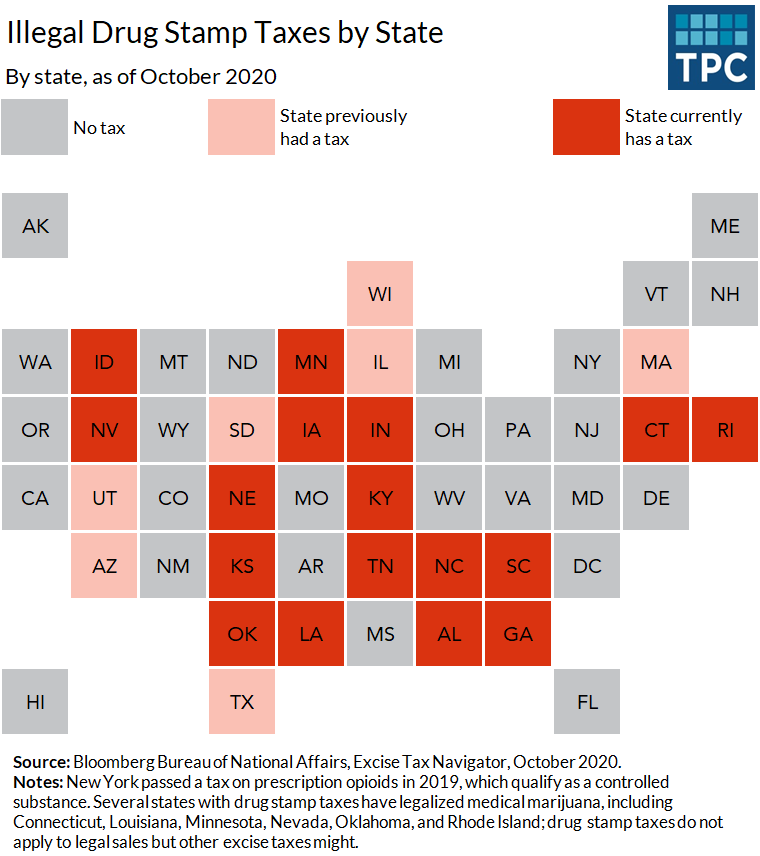

Not surprisingly, very few people voluntarily pay these relatively obscure taxes. Of the 17 states that currently impose a tax on illegal drugs, states that enforce their drug taxes raise small amounts of revenue. But those arrested for drug possession may also face harsh civil or criminal penalties for failure to pay.

State revenue agencies assure residents that the identities of buyers of the drug tax stamps are not shared with law enforcement. This makes tax payments possible, and also reflects historical precedent: states only began adopting drug stamp taxes more than a decade after the original federal stamp tax on “marihuana” was declared unconstitutional in 1969 because it violated Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination.

On paper, these taxes are imposed at specific rates such as $3.50 per gram of marijuana in North Carolina and other variable rates based on weight or dosage units for other controlled substances. However, the criminal justice implications are key to understanding how the illegal drug stamp taxes work in practice.

Paying the state’s drug tax does not make possession of the drug any less illegal, but failure to pay the tax is typically classified as a felony punishable by prison time, a fine, or both.

Even if someone is not convicted of criminal charges for drug possession or tax evasion, they may still face civil (monetary) penalties that vary by state: these can require payments of up to double the original amount of tax owed, as well as interest on the tax owed. Revenue agencies can use all their standard tools to collect this tax, including issuing tax liens, seizing assets, or garnishing wages.

As noted above, actual, upfront sales of tax stamps are rare, indicating that most revenues are collected as penalties after the fact. Nebraska has only sold 225 stamps in three decades. Massachusetts only sold a significant number of stamps after its law was declared unconstitutional; the stamps proved far more popular among collectors than taxpayers.

Therefore, more often than not, what matters are the penalties for not having the drug stamps on the quantity of illicit substances you are caught in possession of, be it as a customer or a dealer; not the stamp tax rate set by the states.

States do raise revenue from these taxes through enforcement of violations. Kansas collected $500,000 in fiscal year 2019, mostly from controlled substances other than marijuana. Nebraska reported $126,000 in fiscal year 2018, up from $22,000 and $73,000 the previous two years.

North Carolina appears to enforce its rules the most aggressively. At one point, its Department of Revenue handled 5,000 to 6,000 enforcement cases a year. The state takes in roughly $8 million annually (0.03 percent of its tax collections) from its unauthorized substance tax, mostly from after-the-fact enforcement. Until last year, it had collected only $35,600 cumulatively from drug stamp sales since 1990.

So why do states do this? One justification is these taxes allow states to collect revenue on the otherwise unreported business profits of drug dealers. Small quantities of illegal drugs are generally not subject to tax, because the taxes were intended for dealers. But drug markets are complicated, and more information is needed to understand whether drug tax enforcement primarily impacts higher-level or lower-level dealers, or even users who do not sell drugs.

It’s important to remember that states enacted drug taxes only starting in the 1980s and 1990s as part of their efforts in the national “War on Drugs.” Proponents at the time argued that it was easier to win civil penalties for non-payment of a tax than to win criminal convictions for the underlying drug crime.

But “effective” tax policy is not always equitable. We do not know how prosecutors use their discretion in bringing criminal charges for drug stamp tax violations and we do not have enough information to assess whether the impacts are racially disparate. But the enforcement of this tax cannot be divorced from a context where Black and Latino individuals experience a disproportionate share of drug-related arrests, charges, and incarceration relative to their rates of drug use and drug selling.

And the structure of state drug stamp taxes may create questionable incentives: for example, Kansas, Nebraska, and North Carolina must allocate most revenues from these taxes to state and local law enforcement agencies, a monetary incentive for them to investigate and enforce drug crimes. As with fees and fines more broadly, perverse financial incentives in the criminal justice system disproportionately impact Black and Latino individuals.

As states have moved to legalize and tax recreational marijuana, taxes on other controlled substances may face an uncertain future. Similarly, convictions for drug tax charges may be relevant in future debates around expunging past marijuana convictions from individuals’ records.

Given the little revenue illegal drug taxes raise, the resources they require to administer, and the inequitable and harmful impacts they enable through enforcement, it is hard to justify drug stamp taxes as good tax policy. So why keep them around?