For decades, the debate over tax reform has focused on lowering rates and broadening the tax base. That is, curbing or even eliminating the annual $1 trillion-plus of special preferences that litter the tax code. The problem is that many policymakers and researchers erroneously focus too much on deductions from taxable income and often ignore many of the exclusions, credits, deferrals, or special tax rates that account for vastly more in foregone federal revenue.

For example, nearly all the base-broadening in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) focused on deductions. The biggest: a cap on the itemized deduction for state and local taxes (SALT)—which raises substantial revenue and, when combined with the increased standard deduction, will discourage millions of tax filers from itemizing.

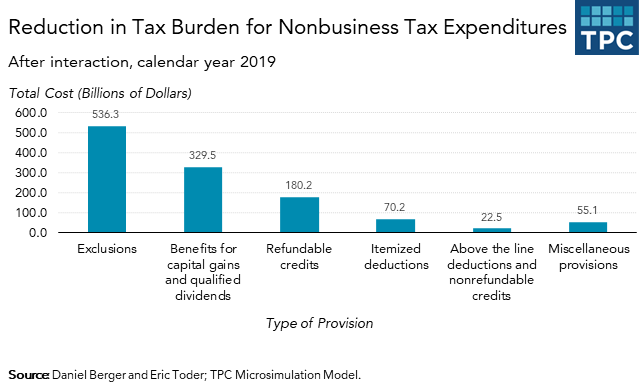

Recent research by Daniel Berger and Eric Toder questions the extraordinary focus on these deductions. Thanks in part to those TCJA changes, itemized deductions are far less important than other tax preferences. Berger and Toder calculate that they now comprise only about $70 billion out of the $1.2 trillion of annual non-business tax expenditures. Prior to the TCJA, Toder and colleagues (2016) figured they accounted for about twice as much—but still a relatively modest $150 billion.

Yet Congress rarely even tries to trim tax preferences other than deductions. Just the other day, the House voted overwhelmingly to repeal the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s Cadillac tax on high-cost employer-sponsored health insurance, a special excise tax that indirectly attempted to scale back the largest of all tax expenditures, the exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance. And that excise tax was enacted under health, not tax, reform legislation.

Why do itemized deductions get so much attention? In part, it is because deductions for state and local taxes, mortgage interest, charitable contributions, and the like are so visible. Many have been around since beginning of the modern income tax in 1913 and some go back to the Civil War version.

Policy researchers focus so intently on deductions for a different reason: That’s where the data are. While the IRS has long reported data on amounts and utilization of itemized deductions, it is much harder to get information on the use of and the amounts associated with exclusions.

It has been a long-standing problem. When the legendary Joe Pechman and Ben Okner, early advocates of tax reform, analyzed who bore the tax burden in 1974 through the first major non-governmental tax model, they had to rely mainly on data reported on individual income tax returns. Thus, their model could not capture tax exclusions, which generally do not show up anywhere on tax forms. When I was at the Treasury Department in the 1980s, I saw how data limitations and research bias limited the knowledge of the economists we recruited as new hires. They may have understood the biases created by the home mortgage interest deduction, but few knew much about the effects of non-discrimination rules in pension plans.

This lack of attention affects policymaking. When elected officials and their staffs fail to develop reform proposals in a data-driven, systematic, and comprehensive way, they are more likely to make choices by whim, or based on selected understanding, or even under the influence of lobbyists.

A few have overcome the problem and focused attention on areas other than itemized deductions.

In 1984, the Treasury Department’s landmark study of tax reform produced a wide-ranging set of proposals that included cutbacks in the tax preferences delivered by exclusions, tax credits, lower tax rates on capital gains, and through other miscellaneous provisions—a far broader focus than just itemized deductions. That study helped set the table for the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

In 2014, then-House Ways & Means Committee Chair Dave Camp proposed a far-reaching tax reform bill that also targeted a wide range of tax preferences going far beyond itemized deductions. This and the 1984 Treasury plan should have served as the models for the TCJA but sadly did not.

Regardless, with itemized deductions now so modest in size relative to other provisions, future reformers looking to lower tax rates may have no choice but to look to exclusions, deferrals, tax credits, and preferential tax rates. That, after all, is where the money is.

***A correction to the featured graph was made on July 26, 2019.***