Democrats are focused on passing the Working Families Tax Relief Act (WFTRA), and for good reason. If passed, the WFTRA would provide about $85 billion in benefits to about 48 million households in 2019. Rather than making the false choice between supporting work with the earned income tax credit (EITC) or supporting children with the child tax credit (CTC), the bill would do both. But somewhat shortsightedly, the legislation fails to address the personal exemption for dependents, a benefit that was reduced to $0 in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act but is set to return after 2025. Keeping it at $0 (and providing a $500 nonrefundable credit for taxpayers, spouses, and non-child dependents instead) would drop the cost from $1.055 trillion to $0.738 trillion over the 10-year budget window, with little impact to the lowest income households.

First – what would the bill do? For workers without children at home – “childless” for tax purposes – the maximum credit would quadruple and would cover incomes similar to the EITC for workers with one child. For workers with children, benefits would increase by about a quarter. This would address the longstanding issue that workers without children receive almost no benefit from the EITC and provide an additional income boost for low- and moderate-income workers with children. This accounts for about $385 billion of total costs.

The CTC would provide an extra $1,000 boost for children under 6 and allow families to receive the maximum credit regardless of earnings. These changes are highly targeted toward families with young children (where ample research suggests investments pay off) and very low-income families with children (another place research suggests would be a good investment).

The bill would also extend the $2,000 maximum CTC beyond 2025, keeping the credit from reverting to its pre-TCJA level of $1,000. But in the TCJA, doubling the CTC didn’t result in a big benefit increase for many families with children (or cost), because the TCJA also reduced the personal exemption for dependents to $0. For many, the changes were roughly offsetting.

The WFTRA would allow the personal exemption for dependents to return. That’s not a problem, per se, but the exemption is ill-targeted, so why let it return? Unlike the CTC, which benefits all but the highest income families (who phase out of benefits eligibility), the personal exemption tilts benefits toward higher income families. A credit works by first offsetting taxes owed, and then, in the case of the CTC, providing families with a refund of any additional credit owed (though under current law, this refund is limited to just $1,400 of the $2,000 maximum credit; the WFTRA would eliminate this disparity allowing the full $2,000 to be received as a refund).

Exemptions work differently. They reduce the amount of income a person owes tax on. If you’re a low- or moderate-income family, you might already have all or most of your income offset by the standard deduction, leaving little opportunity to further reduce taxes by exempting more income. Our progressive rate structure also means that lower-income families benefit less from exempting income than higher-income families. The value of an exemption is tied to the tax rate paid on the last dollars of taxed income. The highest income families avoid 37 cents of tax per dollar of income exempted while a lower income family avoids 10 cents of tax per dollar of income exempted. That skews the value of the exemption toward higher income families.

If the WFTRA took the extra steps of (1) keeping the personal exemption set at $0; (2) extending the $500 child and other dependent credit that applies to dependents who don’t qualify for the $2,000 CTC, indexing it after 2025 just as the dependent exemption will be indexed under current law; and (3) allowing taxpayers and spouses to claim the $500 nonrefundable credit – revenue lost from the WFTRA would be reduced by about $300 billion over the current budget window.

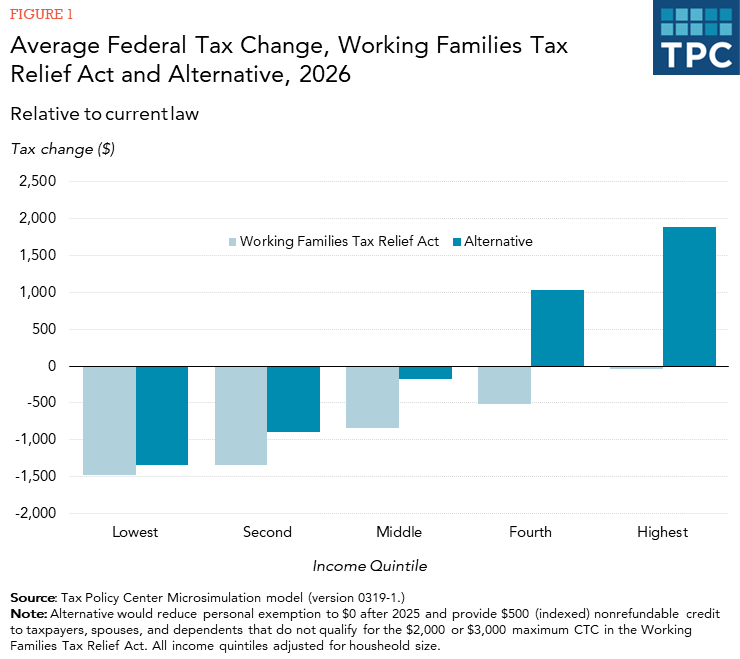

For households with incomes in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution, the average federal tax change would drop from a tax cut of about $1,500 to a tax cut of about $1,350 in 2026 if my alternative were adopted. On average, households in the top forty percent of the income distribution would see their taxes rise, rather than seeing their taxes drop in 2026 (figure 1).

The WFTRA is much lauded for what it’s able to do. But adopting the alternative would keep new benefits focused on the lowest income households, reduce the cost of the legislation, and maybe most importantly—avoid kicking the can on what will happen to the personal exemption further down the road.