Many workers who aren’t raising children are struggling, but there is little to no safety net to help them. And that extends to the tax code, where most provisions for low-income taxpayers are tied to having children. The earned income tax credit (EITC) for workers without children is paltry in comparison to the credit for families with children.

In 2021, Congress expanded the credit for one year. In a recent report, Nikhita Airi, Richard Auxier, and I used new data from the IRS Statistics of Income (SOI) Division to explore who benefited from the temporary expansion. Our results show gains were concentrated among younger workers — historically excluded from the social safety net — and a large share of recipients were in the South. TPC estimates the total costs of permanently reinstating the 2021 expansion would be about $140 billion between 2025 and 2034 and boosting incomes of low-income workers.

Some background

The childless EITC, like the EITC for workers with children, is a refundable tax credit available to workers with low incomes. The credit is often called the “childless” EITC because workers who claim it are not raising children at home, and so are considered “childless” for tax purposes.

However, some “childless” workers do have children but cannot claim them on their federal income tax form for the EITC. These include parents whose children live with someone else during the majority of the year, are 19 or older and not in school full time, or are age 24 or older. Indeed, some estimates suggest that among childless workers 18-64 years old, 40 percent are parents, and 5 percent are noncustodial parents of minor children.

For all workers, the EITC has the same basic structure illustrated in Figure 1. Workers receive an amount equal to a percentage of their earnings up to the maximum credit. Once the credit reaches its maximum, it remains constant until earnings reach the phaseout point. After the phaseout point, the credit declines with each additional dollar of income until the credit equals zero.

Workers with two children, for example, can receive a substantial credit worth up to nearly $7,000 in 2024. In contrast, childless workers can only receive a maximum credit of just over $600. In addition, workers who claim the childless EITC must be between 25 and 64 years of age.

Many of these workers are struggling to pay for basic needs. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that 6 million workers who aren’t raising children at home are taxed further into poverty every year, often because they owe substantially more in Social Security and Medicare taxes than any credit they could receive.

A temporary policy change

In 2021, Congress took a step to helping these workers by temporarily expanding the childless EITC, making it available at slightly higher income shown in Figure 2. They also temporarily expanded eligibility to include 19–24-year-old workers as long as they were not part or full-time students. For these students, the minimum eligibility age was lowered to 24. The maximum age limit of 64 was also lifted. (For former foster youth and homeless youth, the minimum age was lowered to 18.)

IRS data indicate that this expansion led to substantially more workers receiving the credit in 2021 than in previous years, as indicated in Figure 3.

The biggest jump was among younger workers, as indicated in Figure 4. They had previously been excluded from receiving the credit because of their age. (Workers who were part-time students or full-time students in school had to be at least 24 to be eligible for the credit in 2021.)

Many younger workers with modest incomes went from receiving no credit to receiving a credit of nearly $900. And among younger credit recipients, other researchers found this money reduced material hardship and helped these individuals pay for their rent, reducing housing hardships by 28 percent.

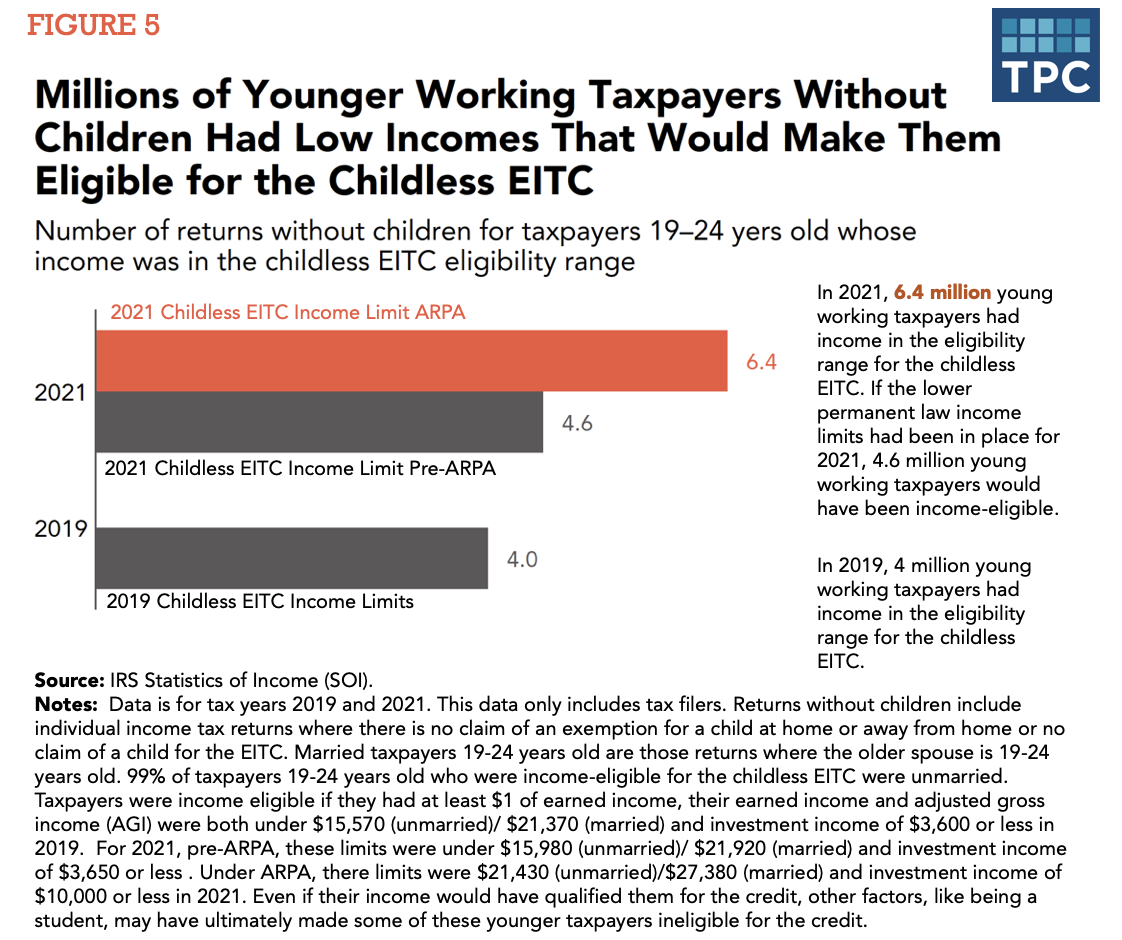

Additional data from the IRS Statistics of Income Division shown in Figure 5 suggest that, in a typical year, many more young working taxpayers with low incomes could benefit from expanding the childless EITC.

Next year’s debates about whether to extend expiring provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provide another opportunity for Congress to consider an expanded childless EITC, an idea also put forth by Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris and which in the past has had bipartisan support.

Compared to the $4.6 trillion cost of extending the TCJA which overwhelmingly benefits those with higher incomes, this would be a modest investment in American workers—younger and older—and reduce material hardships.