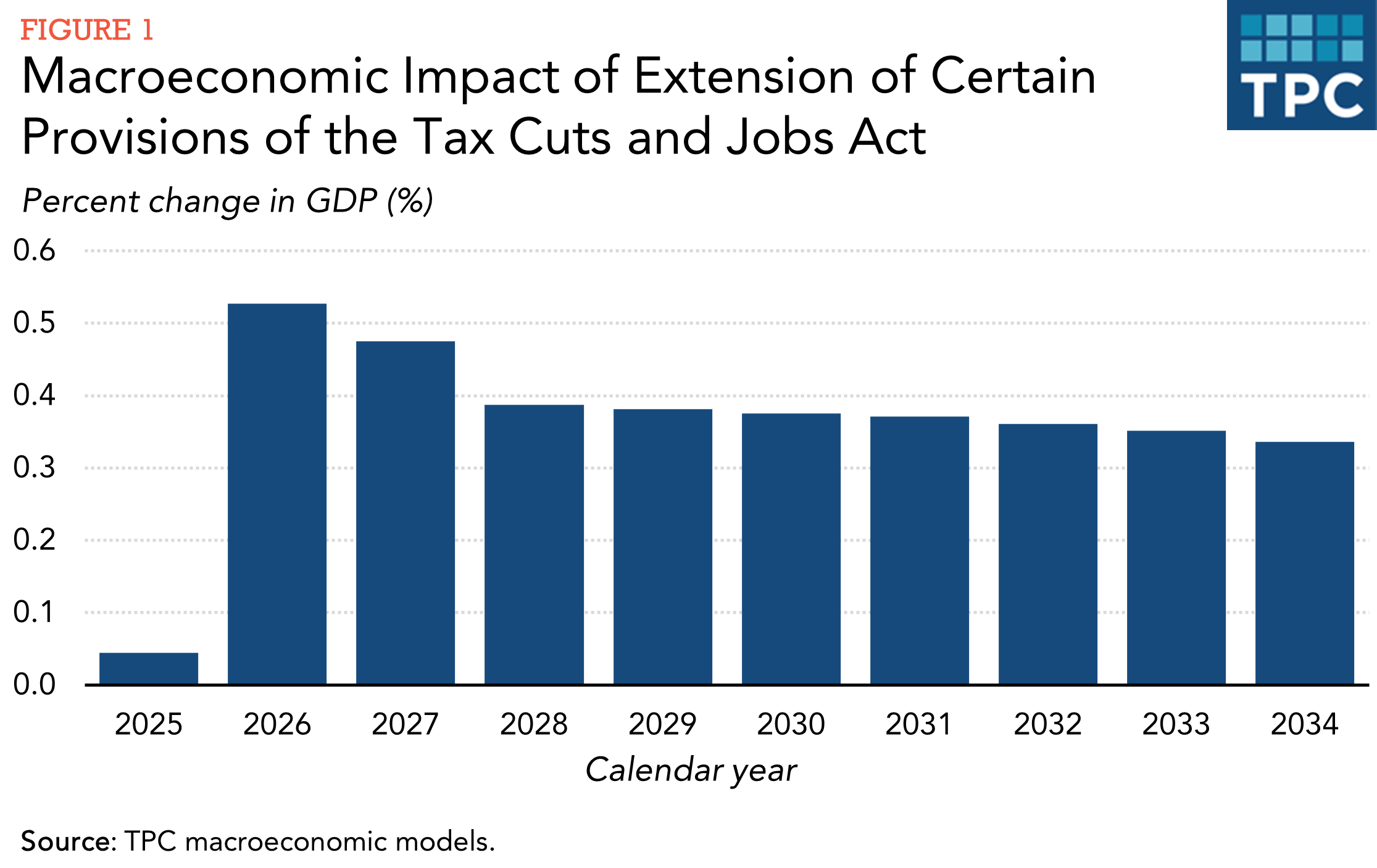

TPC estimates that extending expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) would slightly boost the economy in the short term, increasing gross domestic product (GDP) by about 0.4 percent (click here to download the Excel data file), on average, from 2026 through 2034 (Figure 1). However, over time, these benefits would fade as growing federal deficits reduce business investment. Overall, the economic growth would offset about 6 percent (click here to download the Excel data file) of the $4 trillion cost of TCJA extension.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation have found similar modest economic benefits if only the TCJA’s individual tax cuts (including both lower rates and changes to deductions and exemptions) are extended. TPC’s estimates assume that additional key business provisions of TCJA would remain in place. These include full tax deductions for certain investments (“bonus depreciation”) and more generous international business tax rules.

TCJA extension would boost growth in the short term

TPC estimates that during calendar year 2026, overall taxes would be lower by more than 1 percent of GDP under its extension scenario compared to under expiration. Lower taxes generally mean more money in people’s pockets, encouraging them to spend more on goods and services. This higher demand would prompt businesses to invest in equipment and hire workers to meet increased demand. Businesses would also benefit directly from tax breaks, like full expensing for certain investments, which reduces the cost of upgrading equipment and facilities.

But several factors would temper the economic boost

First, extending the tax cuts disproportionally benefits high-income households, who tend to save rather than spend extra income. Lower-income households spend a greater share of their income. But many of these households owe little to no federal income tax, so they would not benefit from the TCJA extensions until receiving tax refunds in 2027 (through refundable tax credits).

Second, the Federal Reserve would likely maintain higher interest rates to prevent the economy from overheating after this infusion of cash. Higher rates make borrowing more expensive for businesses and households, discouraging investment and spending. These effects would dampen growth after the extension in our model.

Overall, TPC projects that GDP would be higher by about 0.5 percent in 2026 and 2027 under TCJA extension compared to expiration, mostly due to increased incomes. Those effects will be smaller to the extent that the tax cuts are offset by spending cuts, which would reduce or, if large enough, reverse the positive effects on demand. Over time, those short-run effects would fade due to higher interest rates and lower investment and other standard economic responses to those rates, and be supplanted by longer-term effects stemming from changes in incentives.

Longer term, working and saving would be taxed less, boosting output

Extending the policy would lower workers’ marginal tax rates, making work more financially rewarding and encouraging more people to work or work longer hours. Beyond the labor supply, extending the tax cuts would, according to our model, also make saving more attractive due to higher after-tax returns, increasing funds available for investment and lowering costs for businesses. Business tax incentives modeled in TPC’s scenario for TCJA extension would further reduce the cost of investment.

But, rising federal deficits would cause TCJA’s economic boost to decline

While lower taxes generally encourage work and saving, reduced tax revenue would cause larger deficits and increase federal borrowing, pushing up interest rates. This would “crowd out” private investment and slow economic growth over time. This effect would worsen as deficits grow. As in the case of short-run effects, the crowding out effect would be reduced or even reversed to the extent the reduction in revenues due to extension was offset by spending cuts.

Between 2028 and 2034, TPC estimates that the net effect of incentives to work and save and increased deficits would raise GDP by about 0.4 percent on average, mostly due to more investment and more people working (Figure 1). But, within 25 years, GDP is projected to decline as higher deficits take a toll.

The economic boost would raise federal revenues, slightly offsetting the cost of extension

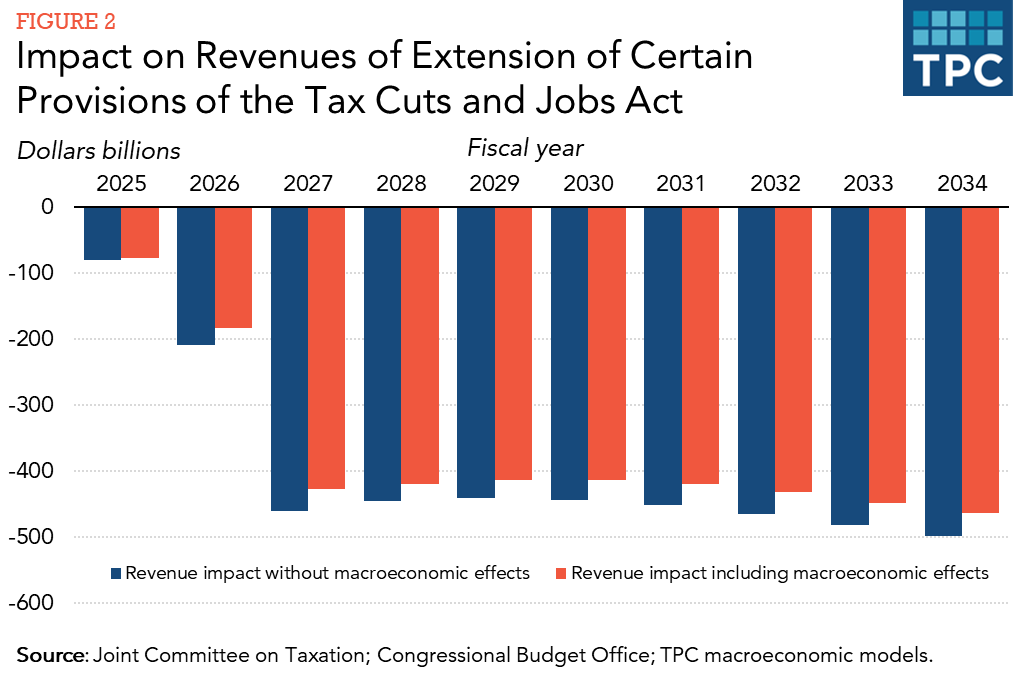

In the ten years after extension, economic growth would boost taxable incomes and offset about $220 billion (6 percent) of the $4 trillion cost of extension from 2025 to 2034 (Figure 2). For comparison, CBO estimates that increased levels of debt under extension would raise federal interest costs by over $600 billion over the same period. (Established scoring practice does not include that amount in the $4 trillion cost of extension.)

Overall, extending TCJA’s expiring individual and some business provisions would boost the economy modestly in the short run, offsetting a small portion of the revenue cost. But TCJA extension would worsen the nation’s already daunting long-term budgetary imbalance and eventually reduce output and incomes. Policymakers should consider those tradeoffs in determining how much of TCJA to extend.