Next year, nearly all of the individual provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will expire unless Congress acts. Congressional scorekeepers have estimated that fully extending the TCJA would cost $4.6 trillion over ten years. The Tax Policy Center has shown that, on average, all income groups would get a tax cut relative to current law, but higher-income households would receive a larger benefit.

But it is important for policymakers to understand more than the average impact of TCJA extensions, especially as they consider changes to specific provisions of the 2017 law. Below we unpack how extending each of the TCJA’s major provisions would affect taxpayers in different income groups. The key takeaway is that specific provisions of the TCJA have very different distributional effects depending on a household’s income level.

The TCJA was a sweeping piece of legislation that made major temporary changes to many individual tax provisions, including reducing marginal tax rates, expanding the standard deduction, expanding the child tax credit, modifying the alternative minimum tax (AMT), and introducing a new deduction for businesses organized as pass-through entities (199A). It raised taxes by repealing personal exemptions and limiting itemized deductions.

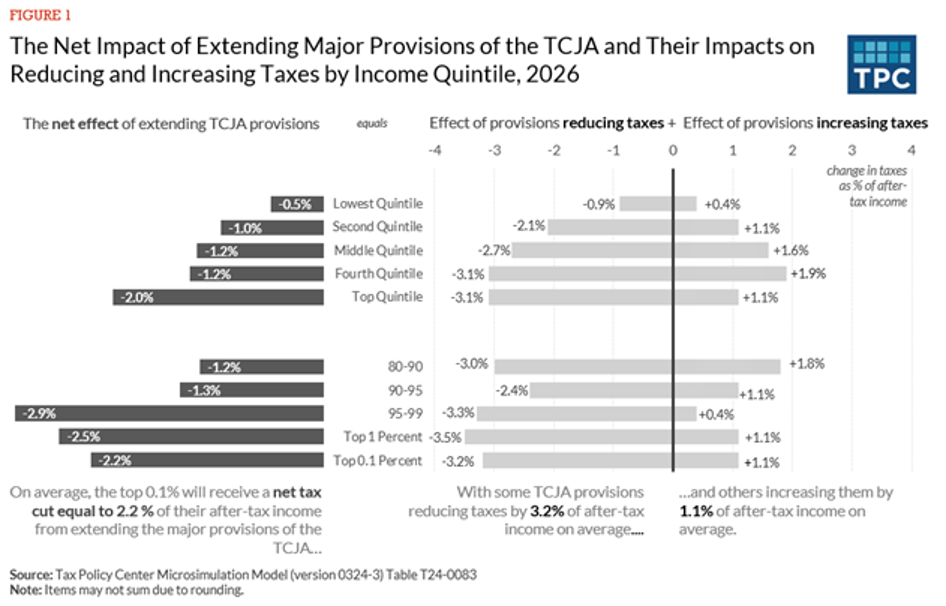

Figure 1 shows the net effect of extending the expiring TCJA provisions (left panel), further breaking down the average effect of provisions that reduce taxes and those that raise them (right panel).

The following figures show how these provisions contribute to the net change in taxes by income group, with positive changes (tax increases) on the right side of the vertical line and negative changes (tax cuts) on the left side and different provisions identified by color.

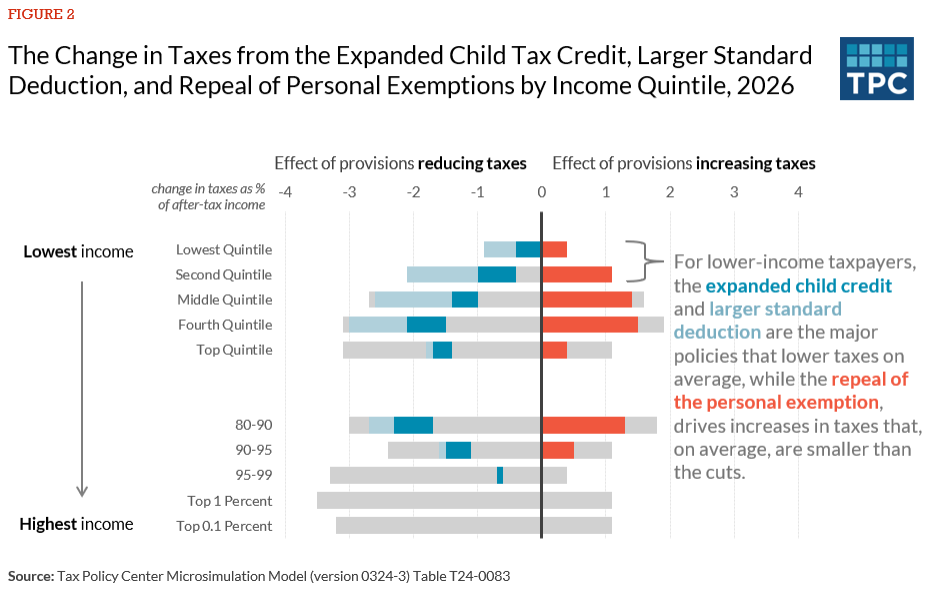

First, low- and middle-income households primarily benefit from the TCJA’s larger standard deduction and expanded child tax credit (Figure 2). These gains are partially offset by the loss of personal exemptions. Taken together, extending these provisions would reduce taxes for households in the bottom income quintile by an average of 0.5 percent of their after-tax income, the net effect of a 0.9 percent income boost offset by 0.4 percent reduction.

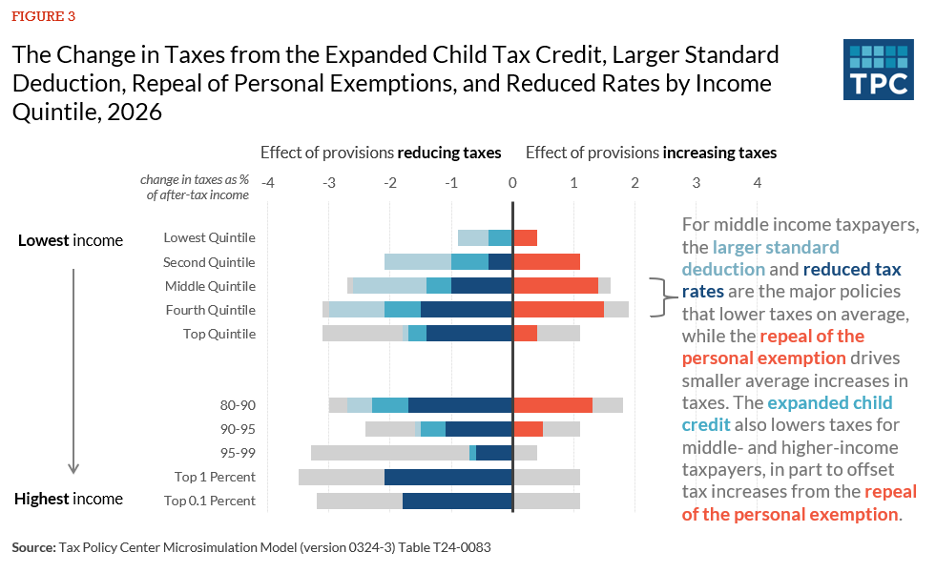

Figure 3 also highlights the effects of extending TCJA’s rate cuts, which provide significant benefits for middle- and upper-income taxpayers. For example, middle-income households receive a 1.2 percent boost in after-tax income from the TCJA extension. This net effect is a combination of tax cuts (totaling 2.8 percent of after-tax income relative to current law) from a higher standard deduction, larger child credit, and lower tax rates, that are offset by tax increases (of 1.6 percent of after-tax income), driven largely by the repeal of the personal exemptions.

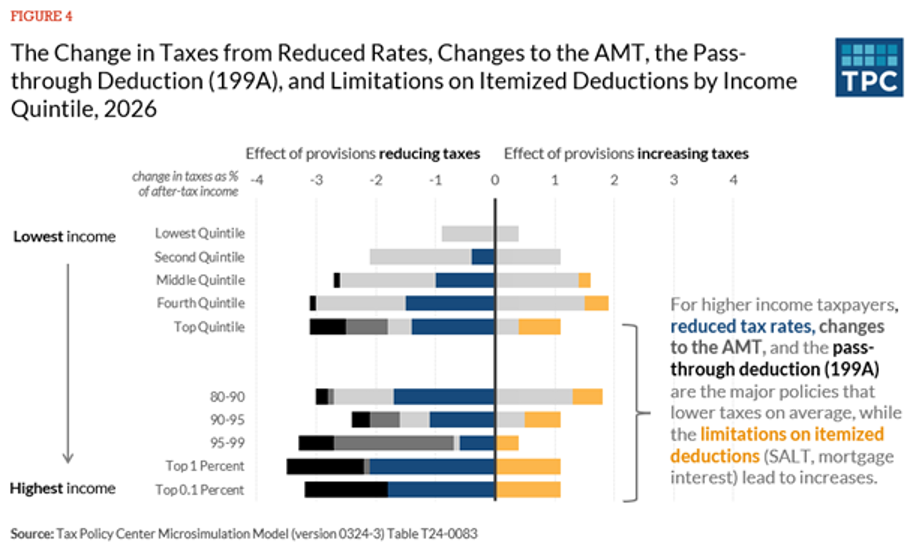

Figure 4 shows the effects of TCJA’s rate cuts along with other provisions that mostly affect higher-income households, including the limits on itemized deductions, changes to the AMT, and the 20-percent pass-through income deduction (199A). The highest-income taxpayers would benefit the most overall from these extensions, seeing net tax cuts of 2 percent of after-tax income for those in the top quintile (2.5 percent for those in the top 1 percent).

The bottom line: the individual provisions of the TCJA involve a combination of gives and takes that affect households differently depending on their income and other characteristics. Unpacking the effect of extending these provisions offers insights about how the overall cost and impact on households would differ if policymakers consider changing the core structure of the TCJA.